Russia

The Holy Governing Synod

The eighteenth century was a period of grave difficulty for the Orthodox Church in Russia. Peter I (the Great) (r. 1689–1725), taking the title of “emperor,” ruled Russia with an iron hand. He became fascinated with Western Europe, especially its advancements in scientific and military technology, and he encouraged the introduction and spread of such technology in Russia. He built the new city of Saint Petersburg on filled in swampland by the Baltic Sea to be Russia’s celebrated “Window to the West.”

As part of his effort to modernize his nation through Westernization, Peter forced the Russian Orthodox Church to accept a radical structural reorganization based on the model of the various Protestant State-Churches in Scandinavia and England. After Patriarch Adrian died in 1700, Peter kept delaying giving his approval for the election of a new patriarch. Finally, in 1721, he issued the Ecclesiastical Regulation. Written by a very Protestant-leaning Ukrainian bishop named Theophan Prokopovich (1681–1738), this document officially abolished the patriarchate of the Russian Church. A standing synod of bishops, priests, and laymen was established in place of the patriarchal office as the highest ruling body in the Church.

All the members of the Holy Synod were appointed by the emperor and were subject to him through its overseer, a government official called the ober-prokurator. A Government-supervised diocesan consistory was set up in each diocese, having more authority than the bishop of the diocese. In effect, the Church administration became an arm of the State. The priests became a kind of caste of lower-order civil administrators.

This radical violation of traditional, canonical Orthodox Church order in Russia—imposed on the church by the emperor—was formally ratified and recognized by the other Eastern patriarchs. This arrangement lasted until 1917, when the patriarchate was officially reestablished at the All-Russian Church Council of Moscow of 1917–1918.

The “Western captivity” of the Russian Church deepened in the 18th century as the seminaries and academies fell more and more under Latinizing influence emanating from the Academy of Kiev. As among the Orthodox suffering under the Turkish yoke, leading churchmen in Russia also tended to be either pro-Roman or pro-Protestant, with those of the pro-Roman school using Roman Catholic arguments against Protestant influences, and those on the other side using Protestant arguments against Roman Catholic influences. Very few on either side plumbed the depths of the Patristic Tradition in order to critique the errors of both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. Hence, the living Tradition of the Church was very much obscured through historical circumstances in this era.

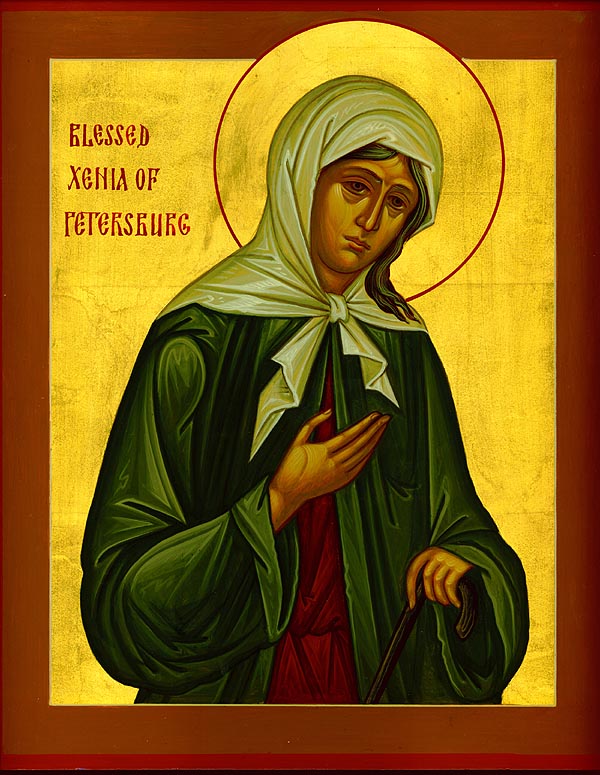

Saint Xenia of Saint Petersburg

By God’s providence, Saint Petersburg, Emperor Peter I’s new westernized, secularized capital city, was not without at least one particularly powerful witness to the truth of the Gospel. Xenia Grigorievna (c. 1730–c. 1800) appeared to have been living a carefree, comfortable, happy life with her husband, an imperial chorister, when suddenly her husband died at a drinking party. She was 26 years old at the time. Stricken with grief at the loss of her husband, she was doubly mournful because they had not been living a Christ-centered life, and her husband had died without having partaken of the holy mysteries of Confession and the Eucharist. She agonized for the soul of her beloved spouse.

Giving to the poor nearly everything she possessed, and giving her house to a friend, she disappeared from the city for eight years. It was said later that she spent those years living with a sisterhood of ascetics, under the guidance of a holy elder. Then just as suddenly, she reappeared in Saint Petersburg, where she walked the streets of the poorest part of the city, the Storona district, and slept in a field under the open sky. She clothed herself in one of her husband’s old uniforms, and from that time on, she took his name, Andrei Theodorovich, as her own. After some time she was granted the gift of clairvoyance, by which she helped many residents of the Storona.

She continued this remarkable way of life for 37 years, until her death at the age of 71. Countless miracles have taken place through her intercessions.

Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk

The most well-known saint of the Russian Church in the 18th century was Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk (1724–1783). Tikhon was a gentle, sensitive, scholarly monk who became the ruling bishop of the vast southern diocese of Voronezh in 1763. He poured his heart and soul into reviving the church life in this diocese, beginning with educating and guiding the clergy, many of whom could scarcely even read, and many were very lax in their fulfillment of their pastoral duties. All of this was reflective of the abnormality of the Church being directly subjected to the State. Exhausted and frustrated from all his efforts and little to show for it in his eyes, Saint Tikhon asked for and was granted retirement from active episcopal work after only four years and four months in the Voronezh Diocese.

For the last 16 years of his life he lived in retirement at a monastery across the Don River. In these years he immersed himself deeply in the Holy Scriptures and the writings of the Church Fathers, especially Saint John Chrysostom. He knew and appreciated, as well, the Pietist writers of the Christian West, who were calling for and writing about a meaningful living relationship with the Living God, over against the barren intellectualism of both Tridentine Catholicism and Calvinistic Protestantism. Saint Tikhon wrote many books giving practical guidance for living the Christian life, including Journey to Heaven and On True Christianity. Through letter-writing he provided spiritual direction and pastoral counseling to many.

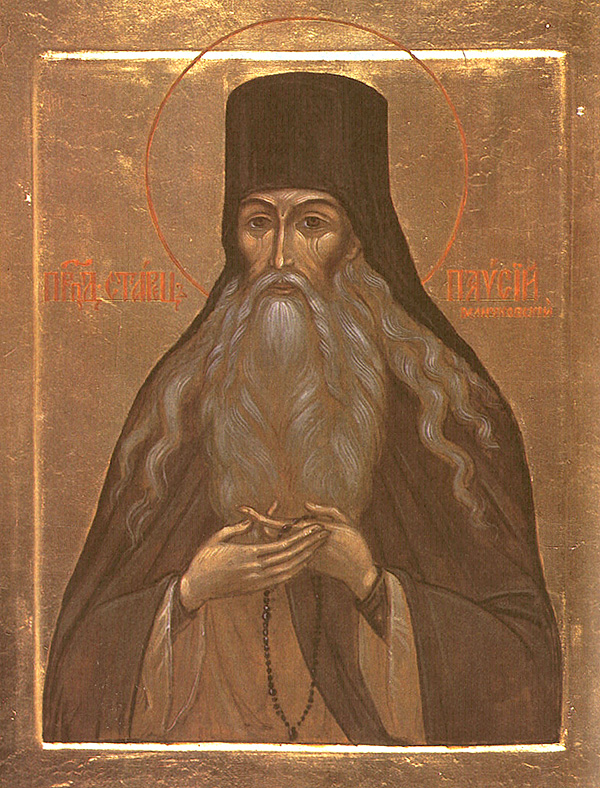

Saint Paisy Velichkovsky

Paisy Velichkovsky (1722–1794) was born into a priestly family in Poltava, in eastern Ukraine. A deeply religious child, he entered the illustrious school at Kiev at the age of 13. However, four years later he fled from there, having explained to the Rector, “I hear only the names of pagan gods and wise men—Cicero, Aristotle, and Plato. By learning their wisdom people of today have become blinded to the end and have digressed from the true way. Intellectuals utter words, but internally, they are filled with darkness and gloom, for their wisdom is of the world only. Not seeing any purpose to such learning, and fearing how I myself cannot but be corrupted by it, I have left it.”

After wandering from place to place for seven years, Paisy reached Mount Athos, where he stayed for about 17 years. Not finding a spiritual father there who could guide him in his quest for direct communion with the living God through hesychastic prayer, he began collecting and translating various writings of the ascetical and mystical Church Fathers. The Fathers themselves became his spiritual fathers through their writings.

In 1763 Saint Paisy left Mount Athos with 63 fellow monks, all speakers of the Slavonic and/or Moldavian languages. Reaching Moldavia, they presented themselves to the Metropolitan of Jassy, who gave them a deserted monastery at Dragomira, which they quickly restored.

Twelve years later, due to the eastward expansion of the Roman Catholic Austro-Hungarian Empire, Saint Paisy and his by now 350 monks fled to the east, where they were eventually given the Niamets Monastery to restore and revive. It was here that Saint Paisy completed his translation into Slavonic of an abridged version of the Philokalia, compiled by Saints Makarios and Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain.

Saint Paisy’s role in restoring the hesychastic tradition in Romania and the Slavic lands cannot be overemphasized. He was one of the first to reemphasize the role of the staretz, or spiritual elder, as a guide in the spiritual/mystical life. This kind of spiritual eldership had fallen into nearly complete oblivion for almost 250 years, ever since the victory of the Possessors over the Non-Possessors in Russia in the 1520s. And besides restoring and/or rejuvenating three monasteries in Moldavia, including leading a community of some 500 monks at Niamets, he so inspired his followers with love for Christ and with a missionary spirit to spread the teaching about hesychastic prayer—this glorious way to intensely experience deep spiritual communion with the Living God—that after his death, hundreds of his followers, carrying his Slavonic translation of the Philokalia, streamed into Russia and spread his approach to the monastic life far and wide.

Metropolitan Platon of Moscow

The leading Russian hierarch of the century was Metropolitan Platon (Levshin) of Moscow (1737–1812). He was an especially eloquent preacher; his collected works include about 500 of his sermons. He wrote a catechism for use by the clergy, and another one for children. More tolerant of the Old Believers than most of his contemporaries, he was the first to allow them to have their own chapels in Moscow, and he formalized the arrangement known as the Yedinoverie (one faith) whereby the Old Believers, upon reconciliation with the Church of Russia, were allowed to continue to worship according to their old rites—though very few of them accepted this offer. He was also the first to write a history of the Russian Church.