The Great Schism in the Papacy, and the Conciliar Movement

The West in the early decades of the 15th century was in turmoil over the relationship between the Papacy and Church councils. Some held that the Papacy was supreme. Others held that the authority of the Church councils supersedes that of the Pope of Rome.

We have already mentioned the beginning of the Papal Schism in 1378, with two men claiming to be the legitimate Pope. In 1409, in order the settle the issue, the Council of Pisa met. This council deposed the two papal claimants and elected a new man, Alexander V, to be the true Pope. However, the two claimants, Gregory XII and Benedict XIII, refused to abandon their claims, so now there were three men claiming to be the real Pope.

This state of affairs convinced the supporters of the Conciliar Movement all the more that another council had to be called to bring an end to this confusion and furor surrounding the Papacy. As a result, in 1414 the Council of Constance met, which would become the pinnacle of the Conciliar Movement. This council, held in southern Germany, deposed all three claimants and then elected Martin V (r. 1417–1431) to be the one and only Pope.

This council, the 16th in the listing of ecumenical councils of the Roman Church, also asserted that even the Pope is to be subject to the dictates of an ecumenical council:

This Ecumenical Council has received immediate authority from our Lord Jesus Christ; and every member of the Church, not excepting the Pope, must obey the Council in all matters pertaining to faith, the putting down of schism, and ecclesiastical reform. If, contrary to this canon, the Pope or anyone else refuses to receive this, or any other Ecumenical Council, he shall be sentenced to penance, and when necessary even be visited with legal punishment.

And to further assert the authority of the council over that of the Papacy, the Council of Constance mandated that future councils would be held according to a regular schedule, rather than relying on the good will of the Pope to call one whenever he so desired.

In 1431, shortly before he died, Pope Martin V called a council to meet in Basel, Switzerland, according to the timetable set by the Council of Constance. But his successor, Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447), was determined to resist the authority of this council and to reassert Papal supremacy in the Roman Church.

The Council of Florence

In 1438, as the Council of Basle continued to meet, the Byzantine Emperor John VIII (r. 1425–1448) made a fervent appeal to the West for military aid against the Ottoman Turks, who by now had reduced the size of the Byzantine Empire to little more than the city of Constantinople. Independently, both the Council of Basle and Pope Eugenius offered to pay for the Greeks to come and negotiate the basis for a restoration of communion between the Eastern Churches and the Church of Rome, in return for military aid.

Understandably, Emperor John VIII and Patriarch Joseph II of Constantinople were much more accustomed to dealing directly with the Bishop of Old Rome rather than with a council—especially a council that the Pope was resisting! So, very fatefully, they decided to meet with the Pope instead of with the Council of Basle. This decision in itself gave a great boost to the prestige and authority of the Papacy over against the Conciliar Movement.

Pope Eugenius, in order to directly assert his authority over the Council of Basle, summoned it to Ferrara in Italy, which also made it easier for the Greeks to get there. Most of the bishops attending in Basle refused to obey the summons of the Pope. Undeterred, he went on with his small council in Ferrara, and received there the Greek delegation of about 700 people. Early in 1439, this council was moved to Florence, since the merchants there offered to pay its expenses.

The Greek delegation was strongly pressured by both the Emperor and the Patriarch to accede to Rome’s terms for reunion, whatever they might be. So, after long and sometimes bitter debating, the Greeks finally agreed to accept:

- a strong declaration of the Pope as “the true vicar of Christ, the head of the whole Church, the father and teacher of all Christians”;

- a declaration that the filioque, “this truth of faith, must be believed and received by all”—and specifically, that the Holy Spirit “proceeds eternally” from both the Father and the Son “as from one principle”;

- a statement of the medieval Western concept of Purgatory, including the assertion that the souls of unbaptized infants “go down immediately to hell to be punished”;

- the allowance for either unleavened bread (azymes; the Latin custom) or leavened bread (the Orthodox custom) to be used in the Eucharist.

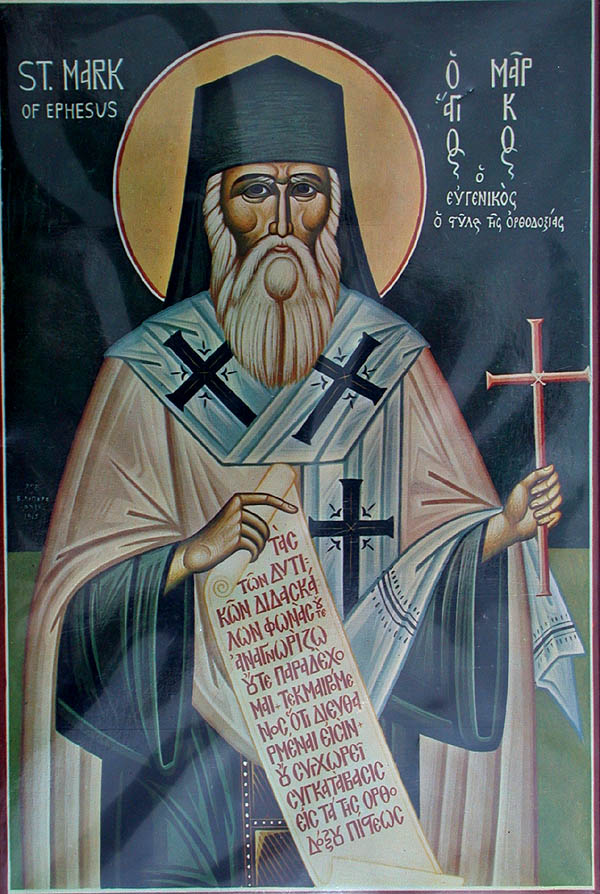

Under severe pressure from the Emperor and the Patriarch, every bishop in the Greek delegation signed this so-called “Decree for the Greeks” promulgated at the Council of Florence—all except Saint Mark, Bishop of Ephesus. When told that Mark had refused to sign, Pope Eugenius is reputed to have said, “Then we have accomplished nothing.” For he knew that Mark’s resistance to the forced union would be the focal point for its eventual rejection by nearly the entire Orthodox world. And indeed, for his courageous resistance to this unjust union, and for his eloquent defense of Orthodoxy over against the errors of Latin Scholastic theology—especially their positions on the filioque and purgatory—he is popularly venerated in the Orthodox Church as one of the Three Pillars of Orthodoxy, along with Saint Photios the Great and Saint Gregory Palamas, who also fought valiantly against Latin aberrations of the Faith.

When the Greek Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev and All Russia, one of the major architects of the Union of Florence, traveled to Moscow to try to impose the Union there, he was run out of the city, barely escaping with his life. Returning to the West, he was eventually made a cardinal in the Roman Church.

Before Saint Mark of Ephesus died in 1444, he entrusted the leadership of the anti-Union party in Constantinople to a prominent, scholarly monk named George Scholarios, who would become Patriarch Gennadios, the first patriarch of Constantinople under the Ottoman Turks. He is remembered in the Orthodox Church as St Gennadios, Patriarch of Constantinople (Feastday, August 31).

The Union of Florence was not publicly proclaimed in the Eastern Church until December 12, 1452, in the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, as the Turks were amassing their forces to begin their siege of the city. Even at that most desperate moment, there was so much popular resistance to the Union that most of the people stood behind George Scholarios, who publicly denounced the so-called “Union Liturgy” held that day. The duke Notaras echoed the opinion of many when he cried out, “We would prefer to see the Turkish turban in our City than the Latin tiara.”